“Hey where the fuck are we anyway today?” a grainy, black-and-white Susan Lowe whines.

“Timonium, I think,” someone replies off-camera.

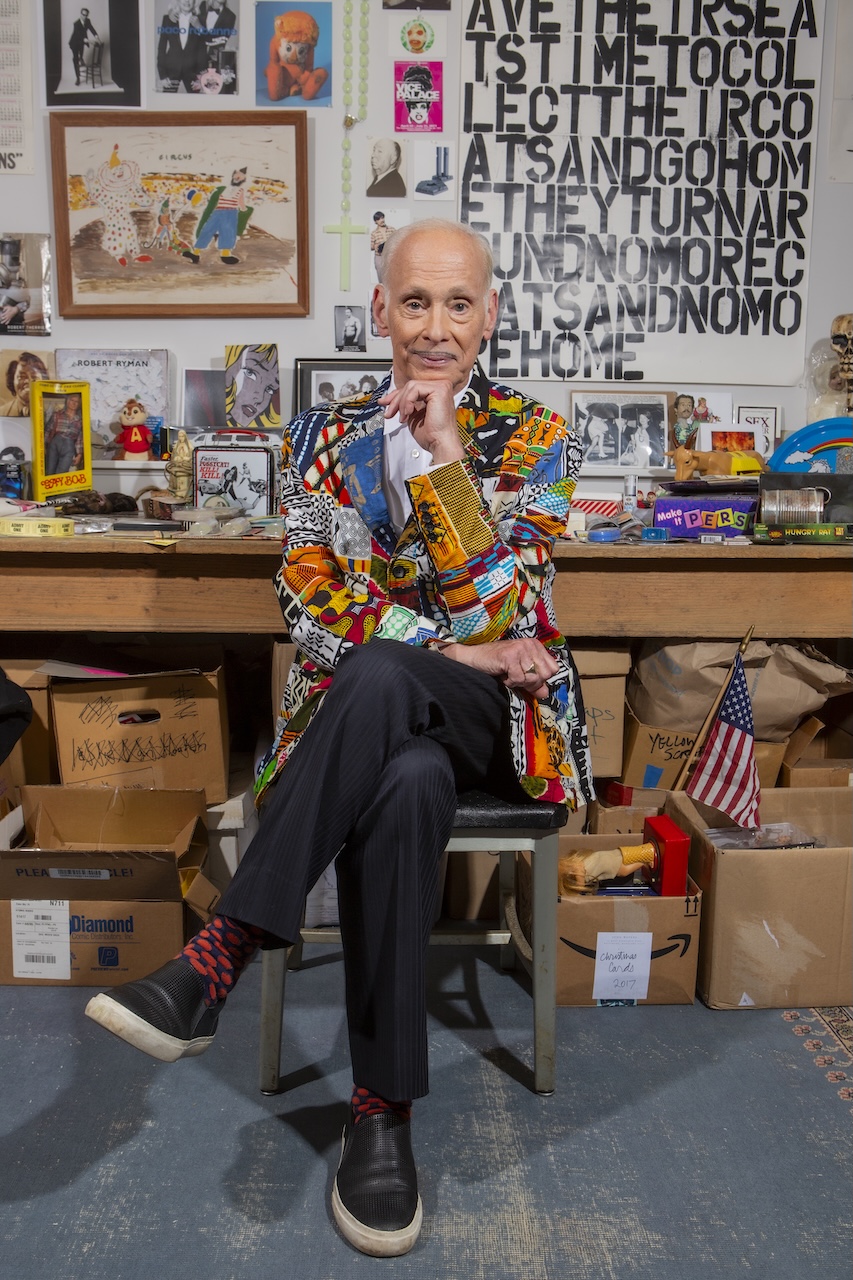

But I am in Barcelona, an ocean away from the strip malls and tract housing of suburban Maryland. It’s the weekly Monday night screening series of queer classics at La Cinètika, an abandoned movie theater squatted by anarchists and reopened to the public as a radical anticapitalist cultural center. Never have I ever felt more like one of the anti-establishment characters in John Waters’ turn-of-the-millenium black comedy Cecil B. Demented. Tonight, though, we’re watching Waters’ Multiple Maniacs, the prolific filmmaker’s first feature-length “talkie” from 1970, often overlooked in his œuvre of more palatable, color, or “polished” films.

I have always been a huge fan of John Waters’ films, visual art, writing, and public persona, but I had never seen this early work. The European audience is packed with fellow devotees who look like they could’ve been styled by “Dreamlander” Van Smith in skin-tight leopard print, biker jackets, Divine eyebrows, and updos of every color. I’m again reminded of just how influential Baltimore’s hometown antiheroes have been in shaping global counterculture and, eventually, even mainstream aesthetics.