The Clifton House is an undeniably majestic figure. Sitting atop Talbot Road, the 117 year old house overlooks the hills and ravines of Gwynn Falls Park from a stony perch. Arriving at the curb I huff my way to its summit—each step unfaltering—both exhilarated and grounded.

This feeling of responding to a call must be a fraction of what Sidney Clifton felt waking up on the ninth anniversary of her mother’s passing to discover her childhood home was put on the market that very morning. And maybe it’s even a fraction of what the owner had felt when the daughter of renowned poet Lucille Clifton reached out about the status of the property. Six years later, the house is growing into a vibrant community art center and cultural ecosystem unto its own. As its programs gain momentum, the Clifton House is already drawing a steady stream of writers and organizers to its front door.

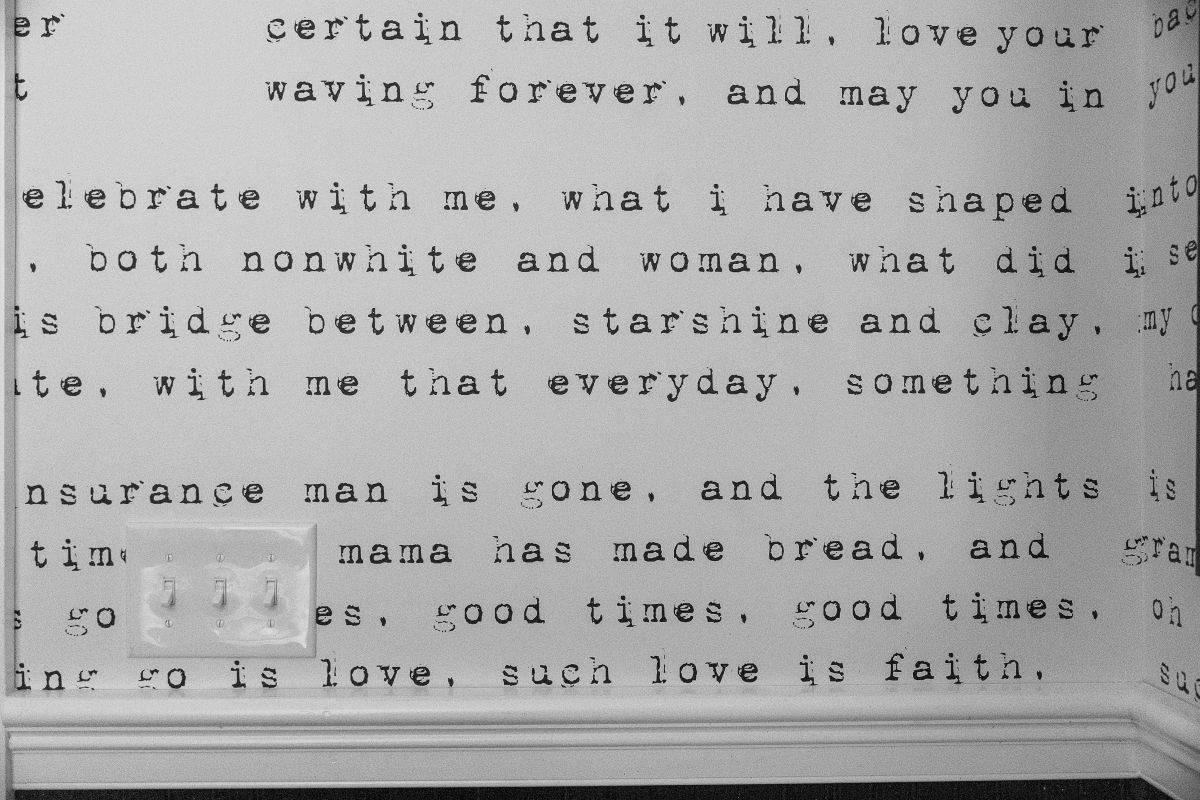

First as homeowners from 1967 to 1980, and now as ancestors, Lucille and Fred Clifton have called many Black artists and activists into their home this way. Lucille Clifton was a legendary poet-in-residence at Coppin State College, earning the title of Maryland’s Poet Laureate from 1979 to 1985 and publishing tens of celebrated titles alongside a stunning collection of children’s books while in Baltimore.

Active in the city, Lucille worked with teenage mothers to publish poetry in Chicory Magazine. She became a trustee at Enoch Pratt Library. Sidney’s father, Fred Clifton, did most of his work behind the scenes as a community activist and professor. His political savvy was matched by expressive and technical talent as a sculptor, critic, and visual artist. Some locally may know him as one of the planners of Dunbar High School relocation. Others might remember his leadership of Maryland’s delegation to the National Black Political Convention.

During the family’s residence they raised Sidney along with five of her siblings, created seminal works, and strategized with elected officials, educators, and other artists to organize political and cultural transformation in Maryland and beyond. The home was blessed by the presence of community—neighbors who would join Fred Clifton for yoga, Lucille listening to the little ones playing in the family room or yard while she wrote at the dining room table. In the hands of the Cliftons, the home became a sanctuary for artists, activists, and children.