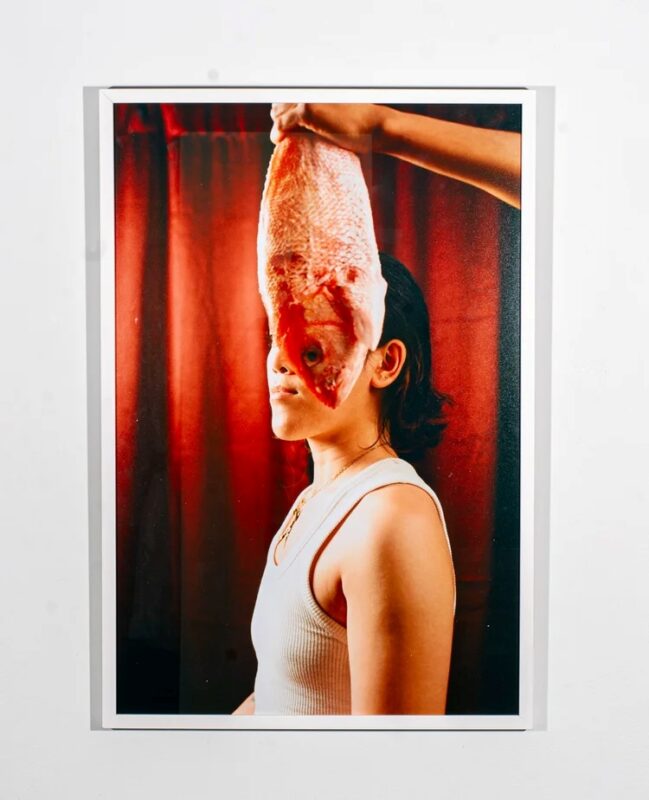

It’s an easy thing to overlook, but quite stunning when we remember it all over again: all art derives, ultimately, from natural materials. Surrounded by digital tools, familiar with synthetic rayons and acrylic paints, and breezily comfortable with conceptual art, we might imagine that art is made from artificial and immaterial elements. But no—for those processing chips, that paint, that ink, and even that gallery space are all made from naturally occurring minerals, from once-living plants and animals, and from the water that covers so much of our earth. Art is, and always has been, a product of the earth.

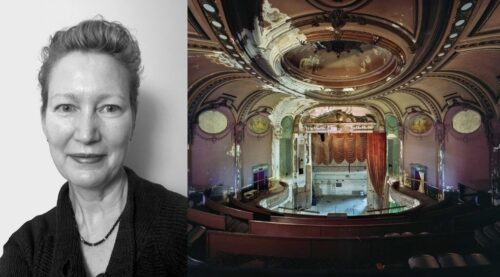

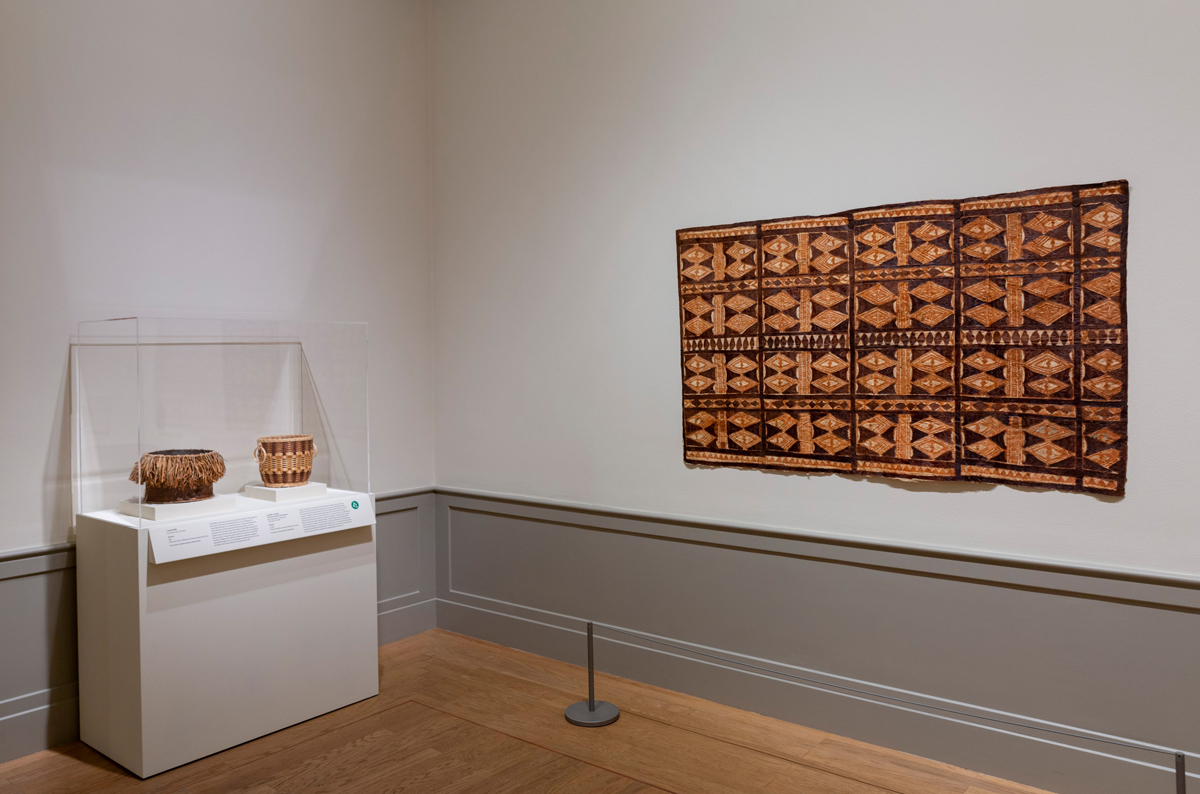

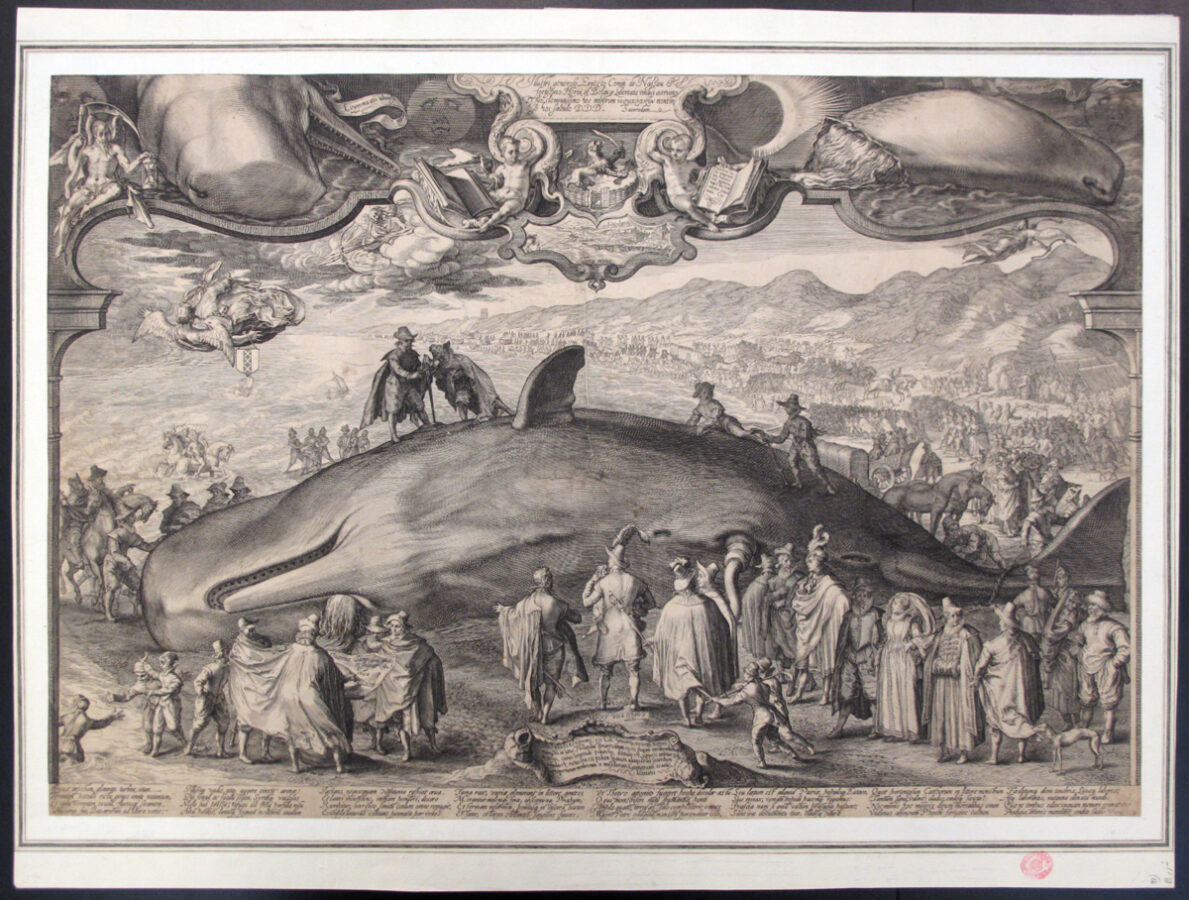

Earth as Medium: Extracting Art from Nature (at the Baltimore Museum of Art through August 17) takes that basic but galvanizing observation as a starting point, and goes on to provide a modest but satisfying sense of some of the ways in which artists have historically drawn on and responded to nature in creating work. Curated by Brittany Luberda and Kevin Tervala, it’s a physically concise show: nineteen objects (all from the museum’s permanent collection, and many likely unfamiliar to most visitors), in one spacious gallery.

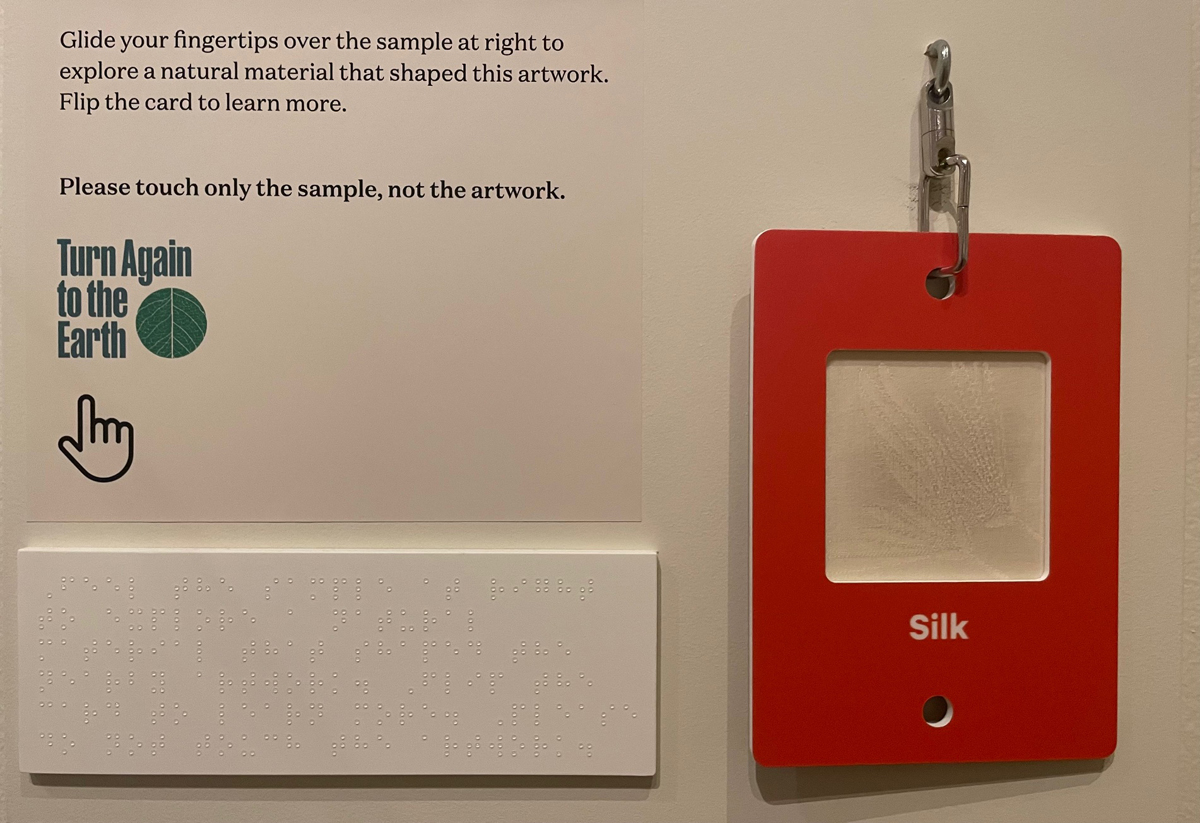

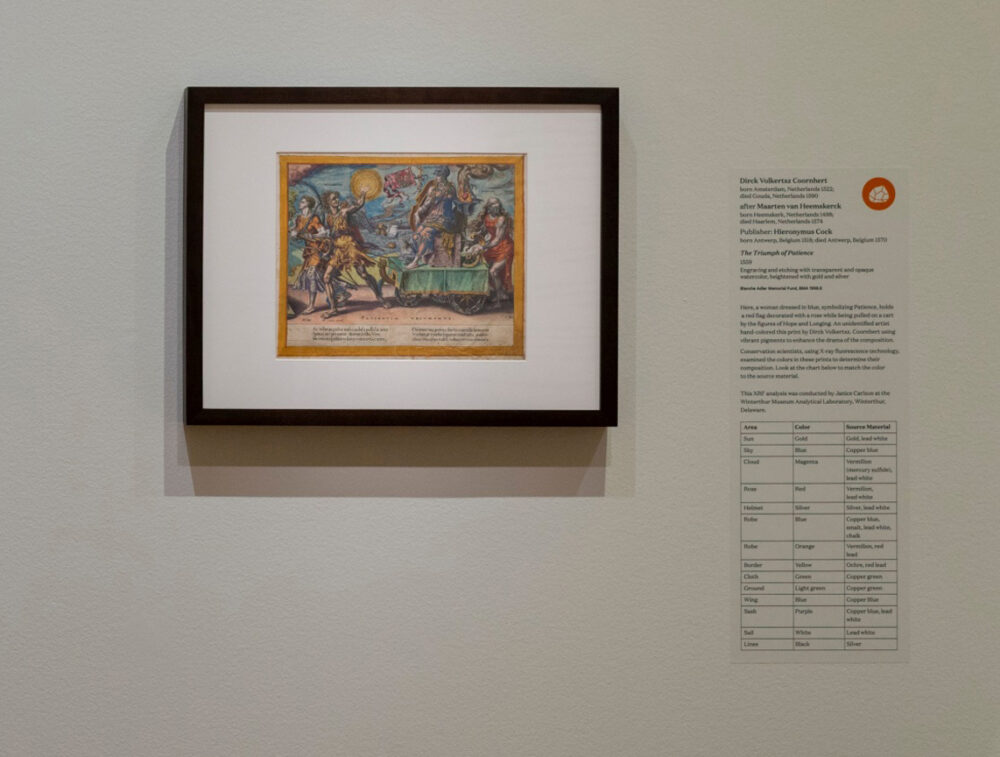

In spirit, though, it’s inclusive and ambitious. Featuring pieces made in six continents and a range of media, the show is gently divided into three sections that emphasize mineral, plant, and animal elements. The wall texts do a fine job of contextualizing the works and accentuating specific materials, while three swatches encourage viewers to touch samples of silk, copper, and painted bark cloth. Three QR codes, too, lead to interviews with historians and makers, who underscore the place of materials in larger patterns of cultural transmission and change.