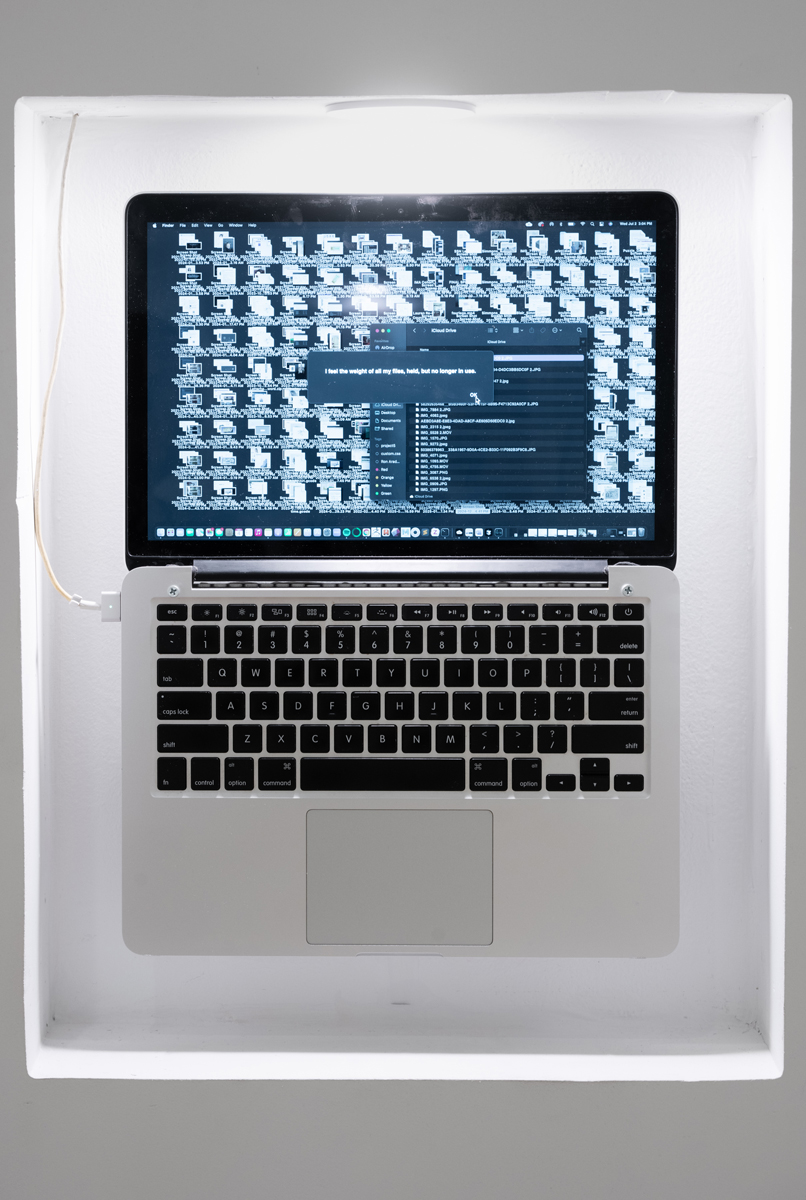

Sculptor and coder Blair Simmons finds kinship with the more-than-human world by humorously probing the limits and failures of machine memory. In “…/documents/files/memories/digitalhoard,” Simmons displays her college MacBook Pro on the wall, activating its personality through an HTML program that enables it to ask viewers for help deleting files. She explains, “I want my computer to forget like I do.” Yet the task is too great, its files too numerous.

While this MacBook Pro feels animate and burdened, across the gallery, an embalmed laptop in “Portrait of Phil Caridi From Ages 30 to 39” could be mistaken for a stelae or architectural fragment. Similarly, “Portrait of Matt Piazza from Ages 24-26” appears fossilized. A sliver of metal peaks through the geologic material, curving into the familiar form of an iPhone. Part of Simmons’ series Archive of Digital Portraits Cast in Concrete, this work and the eight others in the gallery subvert the viewer’s expectations. Intentionally resembling museum artifacts, her sculptures combine obsolete personal electronic devices, “unwiped data”, and cast concrete. By mimicking the aesthetic of the fossil or artifact, Simmons offers institutional and social critique. Her work asks: what do we use, store, remember, value, and discard—and where does it go?

Take the “Portrait of Matt Piazza.” At first, it appears to be a rock. How could a rock be a portrait? Simmons challenges a Western logic of animacy—rooted in Aristotle—that defines rocks as non-living. If a portrait traditionally depicts a living human, Simmons equates a human with concrete, disorienting that species hierarchy. Then we see the iPhone—once Piazza’s, now entombed. An extension of himself in the form of machine memory, it is also a product of global extraction and labor, particularly in the Global South. Simmons’ preserved fragments expose cycles of consumption and waste, urging us to think with the technological and geological worlds we so often overlook.