Just a few weeks ago, on a rainy Lyft home, I was sitting passenger side to an older Pakistani driver, eavesdropping on his conversation with the Dutch newlyweds in the backseat, when news broke about a New Rochelle man testing positive for coronavirus. The driver quipped about the couple’s ill-timed honeymoon and we laughed. We shared our amusement at the novel sight of face masks and offered up theories on “community spread.” At the red light after the couple’s drop-off, the driver took a used Clorox wipe to his steering wheel while I suppressed a cough left over from a recent cold. The rain had stopped, but the skies would remain gray into the evening.

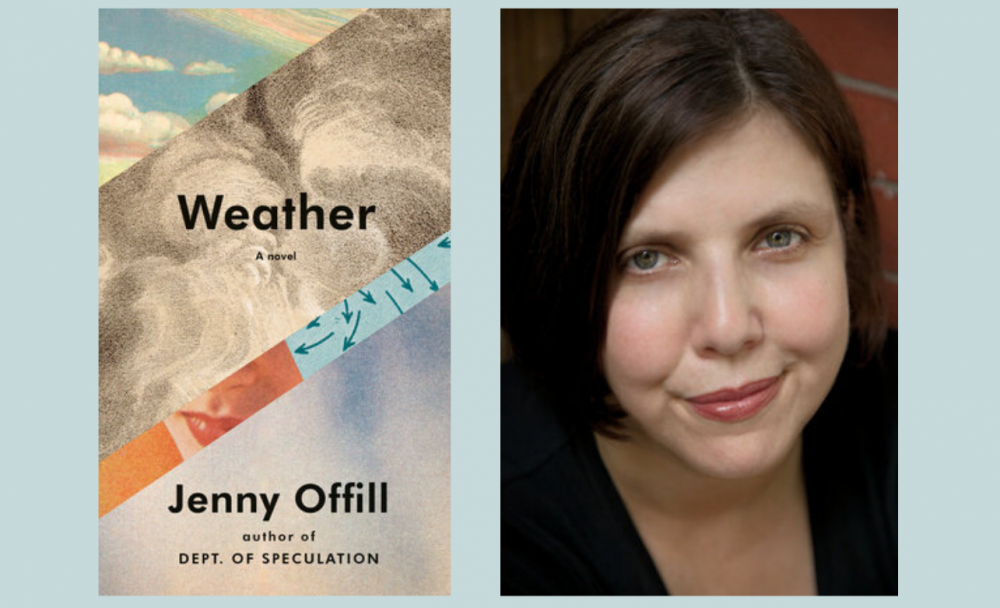

Dreary is the forecast for most of Jenny Offill’s third novel, Weather. Yet Offill delivers news of the coming doom in clear, piquant prose, arranged as glimmering diaristic fragments akin to her previous novel, Dept. of Speculation. Entries spanning no more than a page set the everyday against scholarly dispatches from scientific history, theology, and folklore. Where Speculation explores the interiors of a troubled marriage, Weather takes an atmospheric view of dread, from domestic to existential, that is particular to our 21st-century life.

In 2016, the impending apocalypse preoccupying the narrator, Lizzie Benson, is not ushered by human disease but by climate change. Years after giving up on grad school, Lizzie signs on as part-time assistant to her former mentor, Sylvia, a celebrity amongst climate activists and doom preppers alike. Her job mostly entails responding to listener emails for Sylvia’s podcast, Hell and High Water, a title “guaranteed to attract the end-timers.”