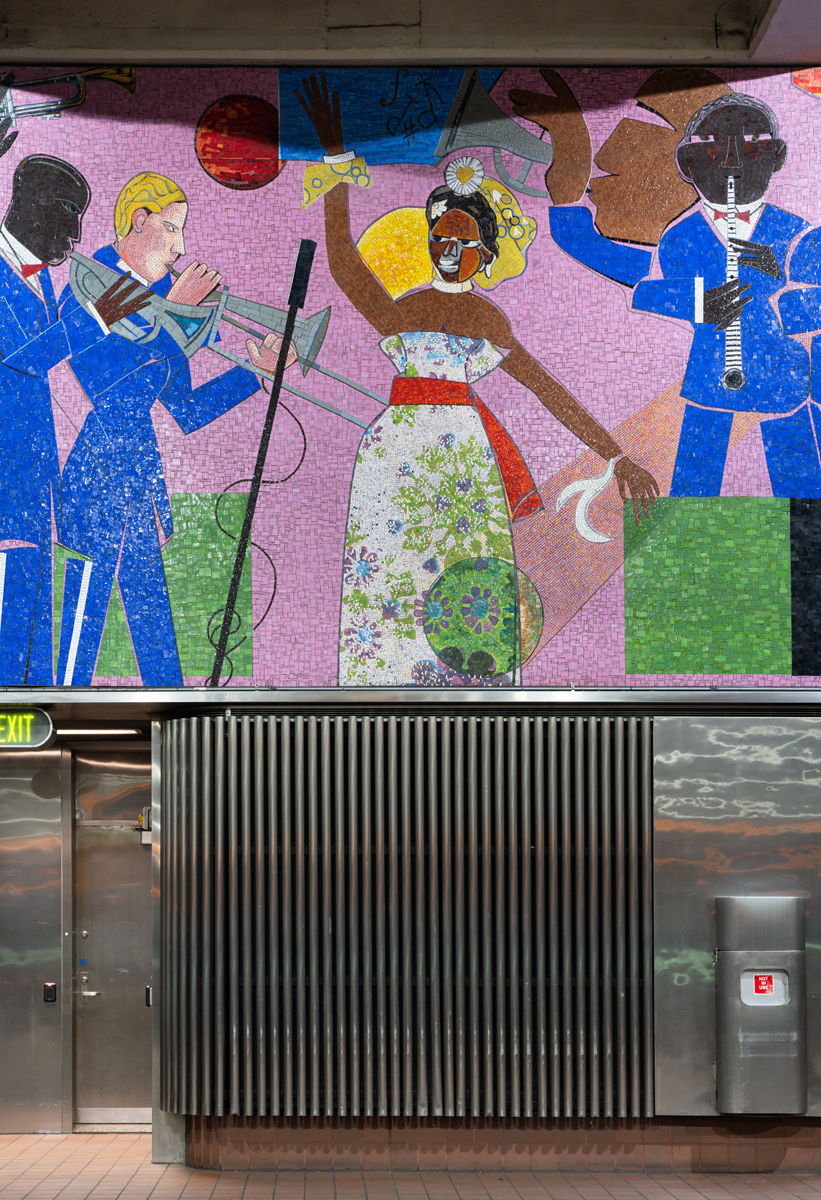

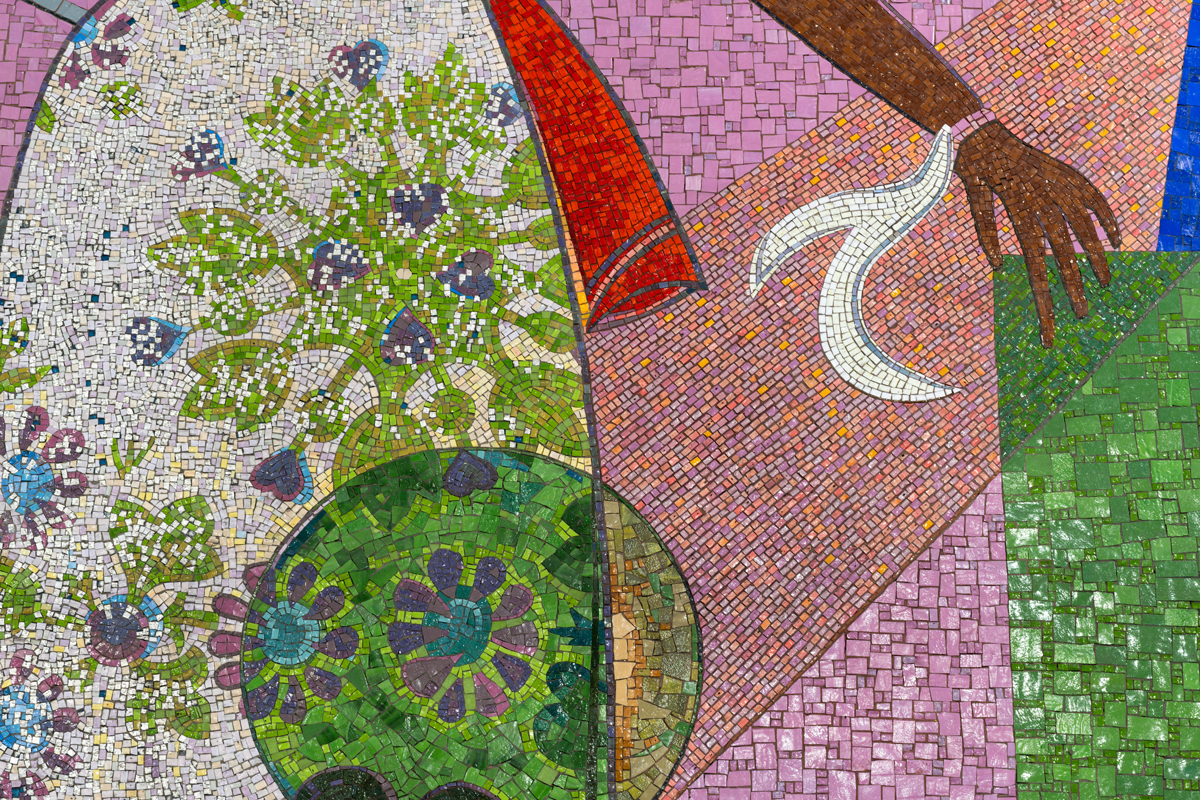

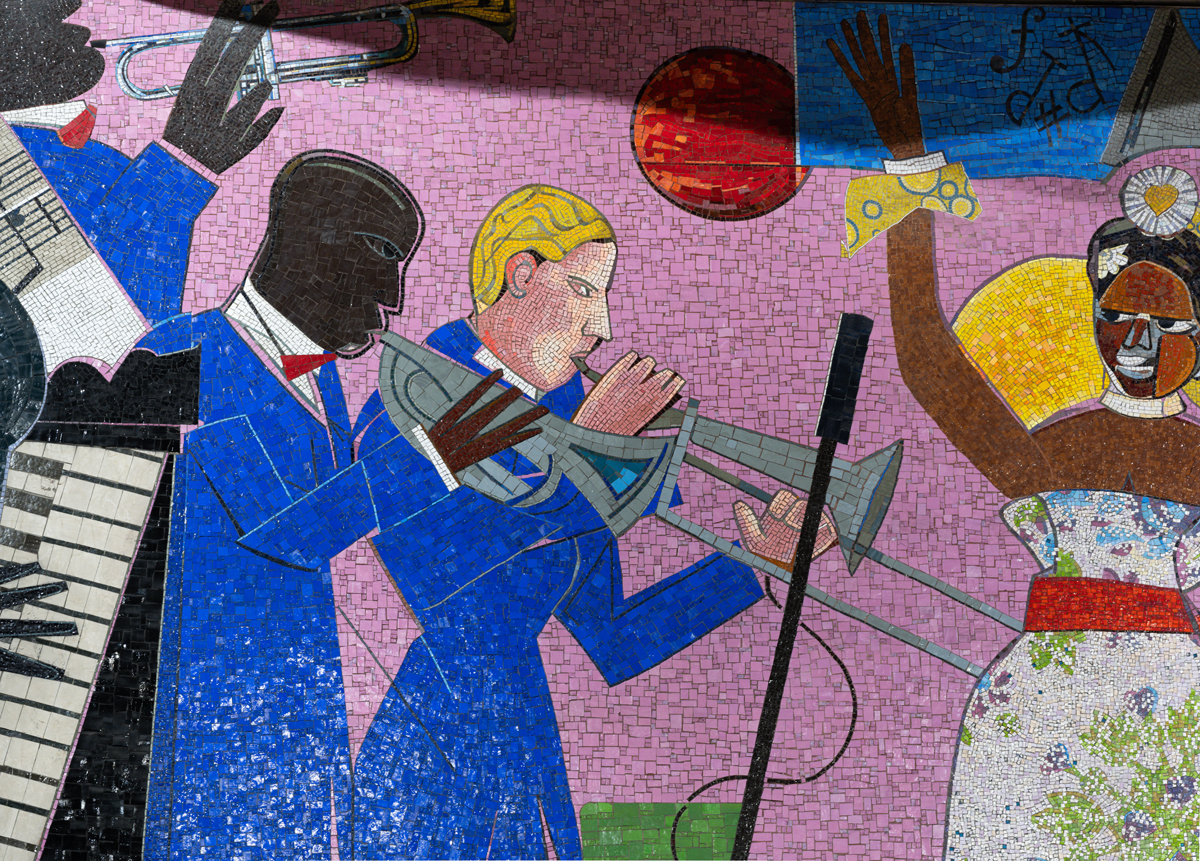

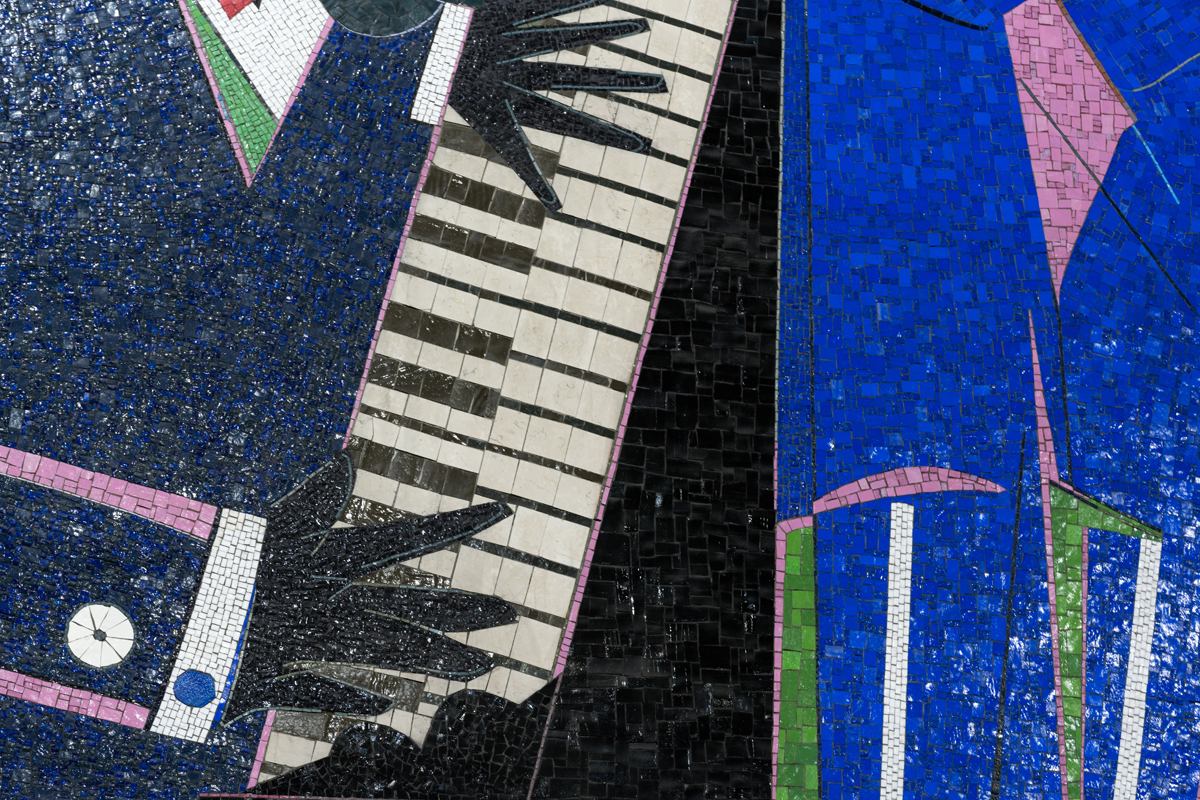

My two favorite public artworks might just be considered verboten by the standards of Trump’s America yet somehow skirted the censors forty years ago: Romare Bearden’s Baltimore Uproar mosaic, unveiled in a metro station for the largely-demolished Upton neighborhood in 1982, and Scott Burton’s gesamtkunstwerk Pearlstone Park, inaugurated in 1985.

Most readers have probably passed through Pearlstone Park—a tidy, oddly-shaped, narrow slice of public space—on their way to the Symphony, MICA, or the light rail. It’s likely that they never considered it’s an artwork—let alone one that’s probably about anonymous gay sex by an artist just now experiencing overdue art historical attention.

Comprising a colonnade of lamp posts and chunky concrete benches arranged in a crescent that reflects the curved facade of the Meyerhoff Symphony and hugs the steep hillside leading down to the MICA Station Building’s parking lot, Pearlstone Park looks innocent enough. It’s a seemingly inoffensive bit of transitional postmodern landscape architecture that physically and aesthetically forms a satisfying link between the brutalist concert hall and the Romanesque former train station across Preston Street.

Indeed, it was Joseph Meyerhoff’s grandson, Richard Pearlstone, who commissioned the park shortly after the symphony named for his grandfather opened in 1982 to resolve the irregular block sandwiched between the hillside, train tracks, institutional buildings, and awkward intersections. But Burton was no ordinary landscape designer. The conceptual artist (and art critic) had cut his teeth in Provincetown and New York’s queer scenes in the preceding, promiscuous decade through performances informed by sexual encounters and functional sculptures that could be described as kinky furniture. Pearlstone Park represented his first major site-specific public piece at this scale.