Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue in C Minor, Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, No. 2, BWV 847 uses just three voices to elaborate on its searching, yearning melody and more melancholic counterpoint, its intricate rhythmic juxtapositions, and its deeply felt harmonic tensions and ultimately transcendent resolution. In performance, the fugue lasts only about a minute and a half—but, as with arguably any individual Bach composition and certainly his canon as a whole, it feels like the kind of thing in which you could lose yourself forever. The resonances stretch out into eternity.

The story of Linling Lu’s arrival at the present moment encompasses many more than three voices, but it carries resonances with Bach’s work. This can be sensed literally, in the interplay of harmonic consonance and tension among the voices that have guided and inspired her, as well as metaphorically, in the way these inspirations step forward into prominence at specific moments and fade into the background in others—toward their ultimate resolution in a body of work that also touches the eternal.

Presently, most days, Lu can be found in her bright, exquisitely well-organized Woodberry studio, immersed in the music in her headphones and in the patient, methodical work of painting another composition. Her monumental series in progress, One Hundred Melodies of Solitude, has now expanded well past its title to comprise more than 260 individual pieces.

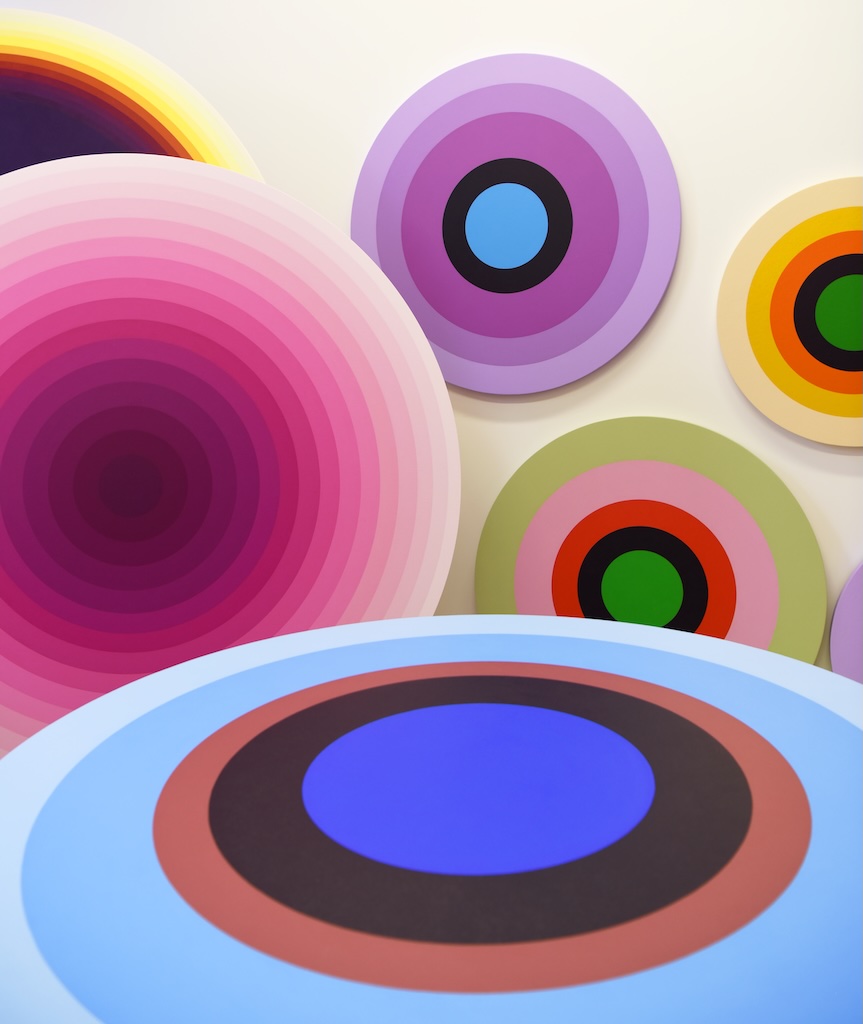

The new paintings, like all the works in the series, are tondos rendered in perfectly even and uniform layers of acrylic. Few or even dozens of concentric circles, varying sometimes subtly and sometimes dramatically in chromatic gradation, radiate outward from or converge inward toward a perfectly even and uniform monochrome center. They seem to shimmer and undulate, these circles, like ripples from a single stone dropped into still water. Deepening in their own cumulative resonance even as they fade, one into the next, these are echoes of sounds, thoughts, visions, dreams, memories.