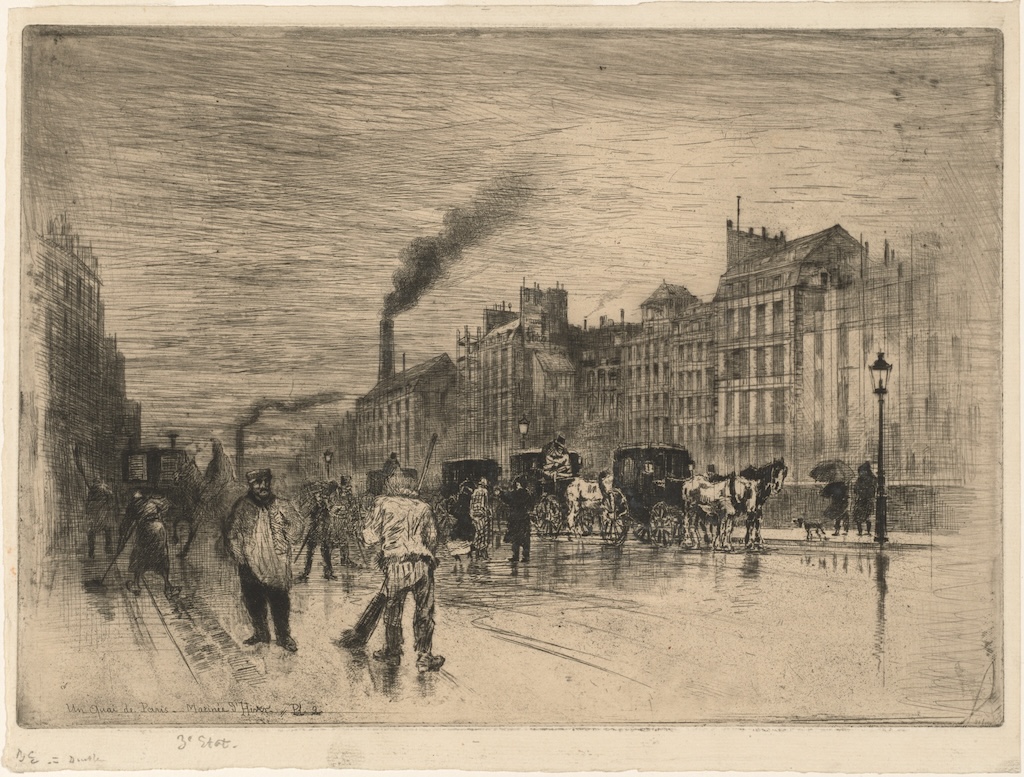

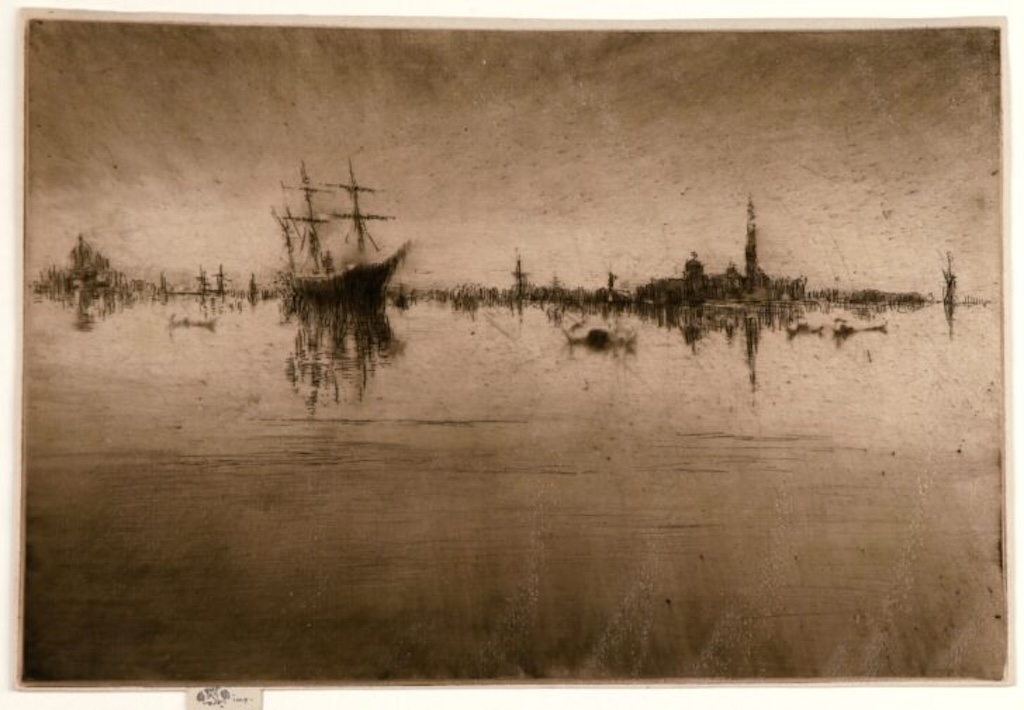

Importantly, though, not everyone celebrated the resulting studies of smoke and haze. One critic, for instance, dismissed Whistler’s tendency to explore dirty side of Venice so frankly. “For who,” he asked, “wants to remember the degradation of what has been noble, and the foulness of what has been fair?”

But Whistler, in turn, could point to the famous writings of John Ruskin, who had critiqued any painters who would “cleanse from their pollution those choked canals which are now the drains of hovels….” Such artists were, in Ruskin’s view, guilty of a failure to look closely and to paint what stood before them, with honesty. Or, as he put it: “instead of giving that refined, complex, delicate, but saddened and gloomy reflection in the polluted water, they clear it up with coarse flashes of yellow, and green, and blue, and spoil their own eyes, and hurt ours.”

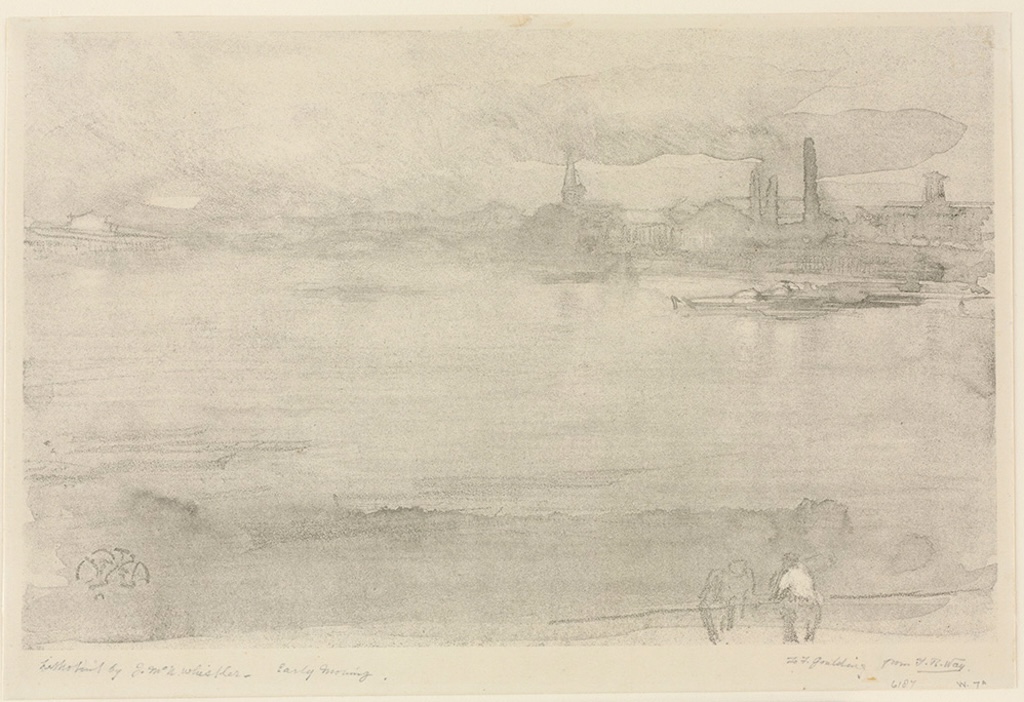

In other words, this was a debate about realism, and the subjectivity of vision. Should one edit (or “read out,” as T.J. Clark once put it) distasteful signs of industrial modernity? Or should one aim at a sort of unaltered transcription of the visible world? To Monet and Whistler, this latter path was often the more rewarding.

Significantly, such an approach also powered George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 “Man and Nature,” widely seen as the first modern environmental treatise. Comparing the observer of ecological change to poets, painters, and sculptors, Perkins concluded that “the power most important to cultivate, and, at the same time, hardest to acquire, is that of seeing what is before him. Sight is a faculty; seeing an art.”

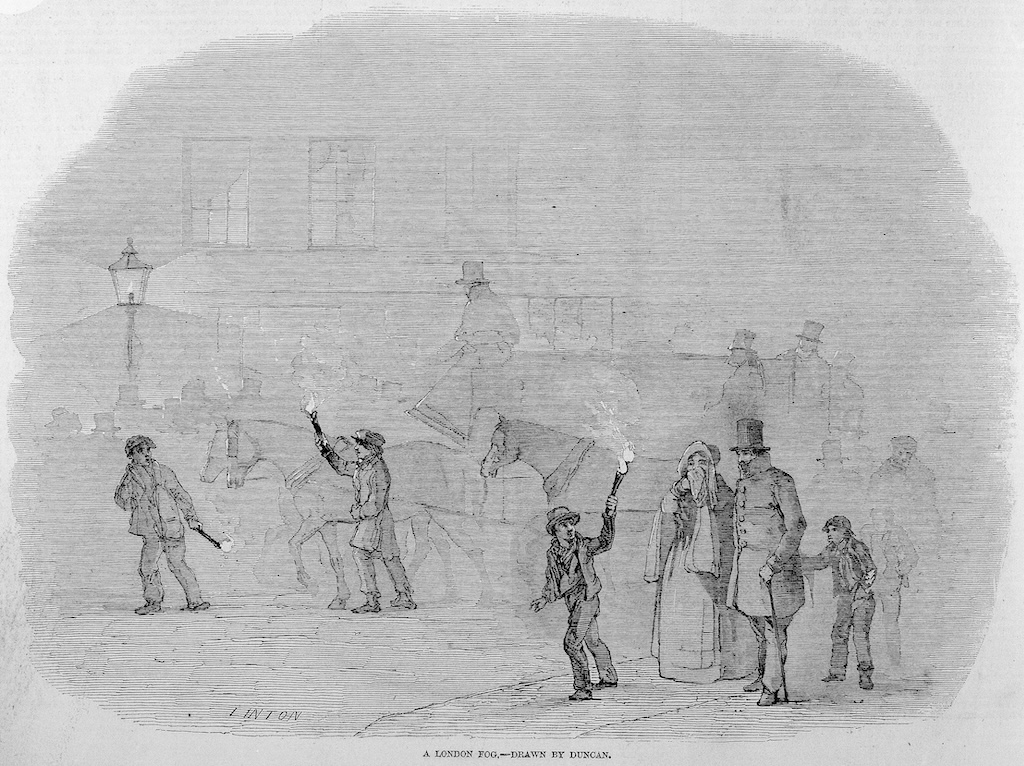

In a sense, then, the artists behind the works on display were lessons in how to see the world that lay before them, with candor and commitment. Monet actually spoke honestly about cultivating such an ability. “My practiced eye,” he claimed, “has found that objects change in appearance in a London fog more and quicker than in any other atmosphere, and the difficulty is to get every change down on canvas.”

In turn, his commitment to a close scrutiny of the world inspired those familiar with his work. In a 1904 essay on Monet’s paintings, Octave Mirbeau exclaimed that “I love smoke with its vitality, its lovely fluidity, its elusiveness, then its disappearance!” Art, it seems, was teaching others to see.

But can it do so today? For air pollution is not simply a thing of the past. While the levels of smog in London and Paris have abated, due to public pressure and responsible legislation, a number of cities around the world, from Hanoi to Milan, continue to struggle with dangerous levels of smog. Indeed, Air Quality includes a clever wall text that notes that the two limestone lions in front of the BMA have been noticeably darkened by airborne sulfur dioxide since they were last cleaned, in 2004. Removing that grime will cost, the museum estimates, $15,980.

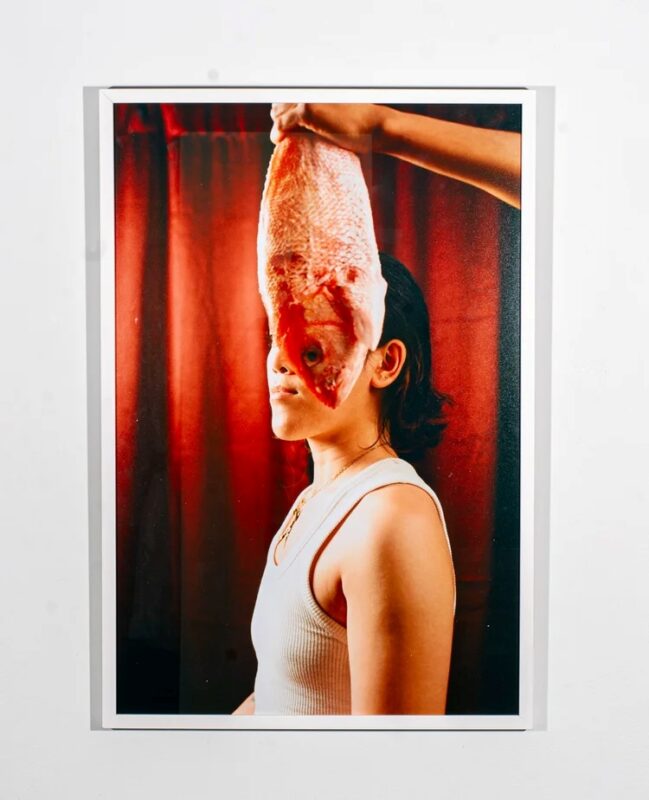

It’s clear that change is possible: public health initiatives can work, and air pollution can be largely eliminated. But it’s also clear that, as Moose put it in speaking of his graffiti work, “the world is really, really dirty.” Ultimately, all of us—the painter who uses industrially produced paints; the curator who flies to Venice to see the Biennale; the critic whose words are stored on energy-consuming servers—bear partial responsibility for that fact.

We may find, like Monet, inspiration in the resulting haze. Or we may seek out, like Matisse, a seemingly brighter alternative. In the end, though, we’re all in this together, and the lions in front of the museum act as a quiet measure of our ability to see what is before us, and an index of our resulting actions—or inaction.