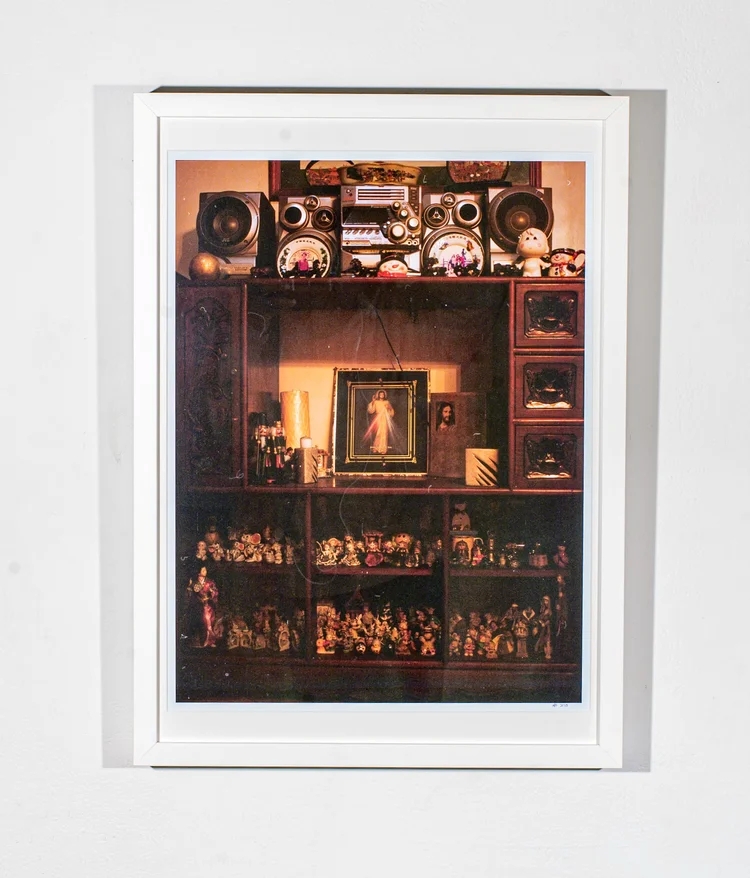

The photographs the artist shot in Baltimore provide glimpses into her home in the US—a voyeuristic peek into her kitchen, her mom’s fridge, and the feeling of home that’s created with chosen family. The fridge is particularly effective in telling a Filipino-American immigrant’s story. Titled “Mom’s Ref,” this interactive work invites viewers to open the doors as you would a fridge and observe what’s inside. A phototransfer of her mom’s actual fridge is affixed to the doors: a riot of souvenir magnets from her mom’s travels, evoking a mix of pride and nostalgia for where she has been able to go. When you open the doors, shelves overflow with stacked tupperware, condiments, tubs of cream cheese, a bottle of calamansi extract, and more.

Open a fridge in a Filipino home and there’s a good chance it’s full to the brim like this. Food is often the love language of Filipino families; the more there is, the more that can be shared. Divinagracia attributed the accumulation of souvenirs and food to what she described as immigrant maximalism. “As soon as you get to a land that has a lot for you, you take a lot for yourself,” she said.

“Mom’s Ref” is one of the artist’s personal favorites—both for what it represents and how it was made. She recalls being in high school and feeling embarrassed when friends came over and wanted a snack, because she feared things would fall out of the fridge when opened. Now she feels a sense of pride and comfort for these details of her lived experience. “That lunch you don’t want to bring to school is the lunch you will end up craving,” she said. Divinagracia constructed this piece with wood, a medium that the artist enjoyed exploring for the first time during the residency, an experience she credits with “unlocking a new level of storytelling that I didn’t know I could have.”

“Prior to being here [at Creative Alliance], I feel like I’ve done a lot of telling other people’s stories, and I think being in here and working for the past few years helped me tell my own story in the way that I would like.” For many first and second generation immigrants, Divinagracia’s story is a deeply relatable one, and in this way, she can feel accomplished in achieving one of her goals: “One of my biggest intentions with this show was to really spotlight Filipino presence in Baltimore and specifically immigrant lives and journeys,” she said. “I want people to feel represented in this body of work.”