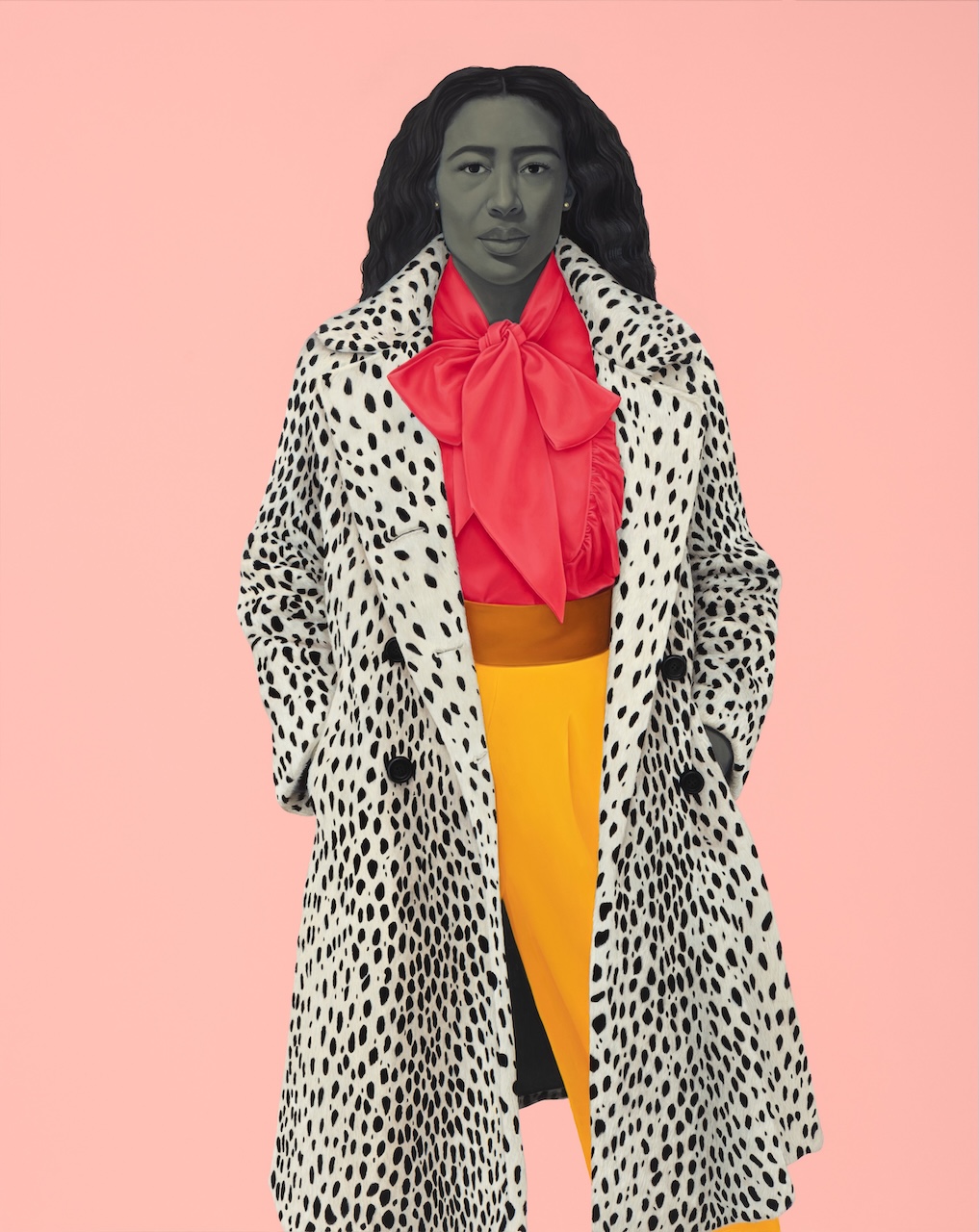

One tiny but important clue in Amy Sherald’s posthumous portrait of Breonna Taylor can be found on the raw canvas on the side of the painting: a scumbled slash of pure cadmium red, peeking out from under the Robins-egg blue background. Although you can’t see the red when looking directly at the painting, the layer adds warmth, subtly alluding to the blood pulsing under Taylor’s luminous skin, rendered in Grisaille, or grayscale.

This strategy of red underpainting goes back to 16th century Venetian painters like Titian and Tintoretto, who used rusty pigments as a base layer to render cool hues more vibrant and fleshtones more lifelike. Coupled with Sherald’s signature Grisaille, a technique used since the Middle Ages to create the illusion of volume on a painted surface, the skin in her portraits of Black American subjects takes on a magical quality.

Now known as Sherald’s signature stylistic move, her rendering of skin in grayscale functions as a metaphor for race in America, evoking Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” and Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” while also summoning the nostalgic elegance of antique black and white photos, transforming each sitter into a modern day icon.

Sherald is a quintessentially contemporary figurative painter, perhaps the most important of our generation. The realization that she deliberately employs, and adjusts as needed, centuries-old painting techniques in order to arrive at images that belong in the art historical cannon is an Easter Egg for art nerds and historians; it speaks to the deliberate nature of her work.